A Farewell to Arms is shot through with truth and rendered in the simplest prose.

A Farewell to Arms is shot through with truth and rendered in the simplest prose.

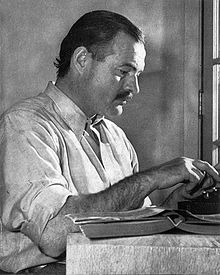

Like a haiku – the ultra-brief Japanese poems lauded for their spare elegance – Ernest Hemingway’s novel about an ambulance driver in World War I uses simple uncluttered language. Landscapes are sketched in a few deft word strokes, death too.

The heartbreak of war is understated. It waits to be uncovered once the reader ponders the words a little. Hemingway called this his Iceberg Theory of writing. The idea is that if you write truly enough your reader will get an innate sense of the story without all the details having to be included for, like an iceberg, much of the story is concealed beneath the surface but accessible.

From a practical writing point of view, Hemingway writes like a newspaper reporter – indeed, he once was one. He describes what he sees in front of him directly and without embellishment. In some of his later works, such as A Moveable Feast, his language is more lyrical, but in this early work his prose is spare. Hemingway further honed this sparse reporter’s style by writing short stories – a medium that teaches a writer to make very word count, rather like copy writing.

For example, his description of a friend’s death in A Farewell to Arms is recounted in just a few words. Hit by a shell, Hemingway describes his friend biting his arm against the pain of his shattered legs, then calling for his mother as he dies. It is not the kind of full-on graphic image we are now used to but it is a telling one, and once again you have to let the reality sink in.

When it works this spare technique works well, but it is a bit of a slow burn. For example, early in the book, Katherine, the nurse the main character Frederic falls in love with, tells Frederic she was going to cut off all her hair after her fiancé was killed at the Front. You only realise the significance of this when you think historically about how important a beautiful head of hair was to a young woman in 1915. To cut off your hair was to negate your femininity, to tell the world you are effectively a widow.

Always precise

The oft-quoted “Courage is grace under pressure” is an excellent example of Hemingway’s concise and precise use of language.

But this longer quote is stylistically even better, partly because of its judicious and repetitive use of ‘very’: “The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially.”

But spare elegance isn’t all. Even Hemingway realised this. Too spare can be dull, and Hemingway’s style developed over time. But he was always careful to use adjectives and adverbs judiciously.

The memoir about his life in Paris as an expatriate writer in the 1920s, called A Moveable Feast, is more sumptuous in style. But it never becomes over-blown, and given the ‘feast’ is a young man’s Paris it could so easily have been in another’s hands.

Here is a wonderful example: “As I ate the oysters with their strong taste of the sea and their faint metallic taste that the cold white wine washed away, leaving only the sea taste and the succulent texture, and as I drank their cold liquid from each shell and washed it down with the crisp taste of the wine, I lost the empty feeling and began to be happy and to make plans.”

There are a lot of descriptive words here, but they are simple ones: cold, crisp, strong.

Hemingway always retained his preference for the simple words. Here is what he had to say about William Faulkner.

“Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words? He thinks I don’t know the ten-dollar words. I know them all right. But there are older and simpler and better words, and those are the ones I use.”

If you like a simple, direct style you’ll love A Farewell to Arms. It doesn’t have the pace and plot of, say, a detective novel, but the flavour of this surprisingly delicate story lingers. It is also a window into a time, and a war, that shapes us and our world to this day.