(Warning: plot spoilers ahead)

It’s a thriller with a plotline that keeps you turning the page and reading late into the night.

It’s a school story that isn’t about posh boarding school kids.

Its hero is ordinary – average at schoolwork, not very handsome and quick-tempered.

But the book has magic – both kinds. Real magic plus the writing kind that makes children read, completely absorbed, sucking a pencil or with a torch under the bed covers.

Boys who don’t like reading love the book. The aerial football likely helps.

You need to laugh too

I’ve been reading Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, along with the other books in the series, for the first time. I’d seen the films with my children but had been put off reading the books because the first one, while a cracking story, isn’t very well written. But, hats off to JK Rowling, she wasn’t too proud to improve her prose. As she wrote more, her writing got better and better. And her knowledge of how young minds work – and their owners’ behave – is spot on. Did I mention the books are funny too, in the bogeys-blood-and-slime way kids love?

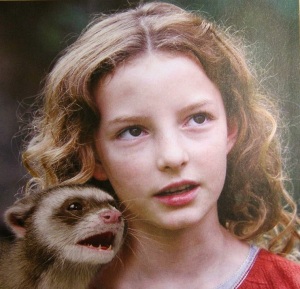

What got me thinking about why the Harry Potter books are so popular is the news that Philip Pullman is set to release a new book set in Lyra’s world of Dust – the world of his acclaimed Northern Lights tale. It was perhaps better named as The Golden Compass, the film of the book.

These magical books – there are three – pull children in too but they’re not in the same popularity league as Rowling’s. I think it’s because they don’t have as many kid-friendly elements as the Harry Potter books. They have a 10-year-old orphan heroine, Lyra – Harry is 10 at the beginning of the first Harry Potter book and an orphan too. The Northern Lights also has wonderful magical animals in its daemons, the children’s animal-companions who are also their souls. But Lyra doesn’t go to school and the book’s aren’t humorous either.

That master dramatist William Shakespeare understood the value of humour. He had funny sub-plots and buffoons. You only have to think of Bottom, bewitched with a donkey’s head in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with whom the proud fairy queen, under an unfortunate enchantment, promptly falls in love.

Philip Pullman is a wonderful storyteller and he writes very well, but marrying a school story, as JK Rowling did (Enid Blyton showed how much children like to read about their school world) with a magical thriller – that’s genius. And a hero who isn’t special, who is really an ordinary boy – children can identify strongly with him. And Harry wants to be even more ordinary and have a family like the chaotic Weasleys, for instance. The Weasleys may live in a tumbledown house but it’s painted with love.

There’s a subtle religious element in the Harry Potter books too – Harry is a sacrifice figure. This isn’t painted large though, and the books are all the better for it. Harry ends up saving the world from grown-up magical bullies, but he’s a most reluctant hero. Lyra is a sacrificial character too. Philip Pullman spells this out in his second book, The Subtle Knife, that she is Eve – an Eve who has to make a big sacrifice. But the religious element in these books is made very clear, perhaps too much so.

Animals and cool kids

Animals – what child doesn’t love them, especially magical ones? There are magical animals in both Philip Pullman and JK Rowling’s books. Soul animals in the Northern Lights, and, in Harry Potter, so many animals – from owl messengers to winged horses only those who have seen death can see, to Hagrid’s terrifying pets. There’s his three-headed giant dog called Fluffy, a baby dragon who wrecks his cabin, and a hippogriffin who eats dead rats. Yup, kids love pets, especially when there’s yuckiness involved too.

A bit of gross humour also goes a long way towards injecting lighter moments into a story. Think Shakespeare and Bottom. The humour is also mostly kind in Harry Potter. There are other humorous children’s writers. Famously, Roald Dahl, who is very amusing but whose humour sometimes makes you feel like you’ve been mentally stabbed.

As a school story, Harry Potter also scores over the much rated (by kids; teachers loathe her) Enid Blyton books. Harry’s world is an inclusive one. Boarding school is expensive but Hogwarts is open to anyone with magical ability. Enid Blyton’s boarding schools – Malory Towers and St Claire’s – are strictly a rich kid’s world.

Then there’s the cool kid element that’s so important at school. Harry is a cool kid but doesn’t realise it – he’s an orphan, after all. His friends, Hermione the swot and red-haired Ron, who comes from a big, poor family, aren’t so cool, although they get cooler as they grow older.

Approval by peers – being considered cool – is vital to children. To see their struggle for approval mirrored in a book, and follow how the characters overcome their individual challenges is so important. Harry, Ron and Hermione’s personal growth is also accompanied by a message about what’s really matters in life. Compare Ron’s home – scruffy and bursting at the seams but glued together by the golden-hearted Weasley parents – to Harry’s godfather Sirius’ home – a rich, bleak London house, once splendid, now empty and dilapidated.

So, there you have it. The reason for Harry Potter’s success: so very many elements and issues that are important to children all in the one story. There’s making friends, dealing with school bullies and real characters who are imperfect – just like you. Then there are challenging but wonderful animals, funny bits, gory bits, enthralling magic and an exciting plot that keeps you asking: ‘what’s going to happen next?’ And there’s Quidditch – an extremely dangerous aerial football game played on broomsticks. What’s not to like?

But it’s how you put it together too. JK Rowling’s writing improved hugely as she wrote more books. She will never be a lyrical writer – Philip Pullman writes wonderful lyrical passages – but in the end what matters more is telling a compelling story that is peopled with characters you care about because they face similar challenges to you. They just have magical powers that they occasionally misuse, sometimes for the fun of it. Who wouldn’t?

Sales numbers seem to support my view of the Harry books – it’s the world’s best-selling book series, with over 500 million sold.

Psst… This is a personal take on Harry and I’ve just been told by my daughter that she knew lots of girls who’d never normally pick up a book who read Harry Potter.